The Economic and Ecological Value of Mountain Lions and Bobcats in the West: Part I

The benefits of wild cats on the Colorado landscape and arguments for human-wild cat coexistence without trophy hunting or commercial trapping

- Dr. Jim Keen, DVM, Ph.D.

A coalition of animal sanctuaries, wildlife rehabbers, animal protectionists, scientists, veterinarians, conservationists, ethical hunters, and concerned private citizens have their sights set on mountain lions — specifically by taking aim at trophy hunting of the big cats. This set of unlikely allies has coalesced behind the principle that killing mountain lions for trophies and bobcats for their pelts is ethically suspect, unsporting, cruel, and scientifically dubious. They also believe it runs at crosscurrents with the collective will of most Coloradans.

To this end, the Cats Aren’t Trophies (CATs) campaign was launched in September 2023. The goal of CATs is to bring the issue of trophy hunting and trapping of Colorado wild cats to the states’ voters via a ballot measure in Fall 2024. The ballot measure, if passed, would ban trophy hunting of mountain lions and the hunting and trapping of bobcats and lynx as trophies or for their pelts.

Mountain lion hunting is legal in many states in the West. In Colorado, mountain lions are usually hunted with hired packs of hounds who tree the lion or trap it on a rock ledge. The cornered lion is then killed by bow and arrow or firearm. (See Can You Hunt and Eat a Mountain Lion.).

In recent years, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) has allowed the recreational killing of about 500 mountain lions annually, with the cats targeted during a three-month season stretching from late November through the end of February. (The Colorado mountain lion population is estimated at 3,000 to 7,000 animals by CPW.) The agency adjusts the mountain lion kill limits every year, with the 2023-24 hunting season capped at 674 animals. (The number of mountain lions killed by hunters during the current Nov. 27, 2023, to March 31, 2024, season can be accessed here.) There are no seasonal limits for bobcats, who can be hunted day or night. The annual toll typically reaches 2,000.

The pelts of many of these bobcats are sold to China, Russia, and Ukraine. Top Western bobcat pelts sell in the $200-$300 range, while lower-end pelts sell for $30-$60. While global demand for fur continues to wane, bobcat pelts are considered to be relatively valuable, especially compared to other furbearer pelts. This is due to the international demand for bobcat fur in the fashion industry, where it is used to make coats, hats, and other garments.

In this essay, I will:

- Summarize the benefits to Colorado ecosystems and human society provided by free-ranging wild mountain lions and bobcats.

- Describe the dubious ethics of hunting and trapping Colorado’s wild cats.

Benefits of mountain lions and bobcats

Mountain lions are apex (or top) predators, defined as a predator at the top of a food chain without natural predators of their own. They play a crucial role in maintaining the health and balance of ecosystems by controlling prey populations and keeping other, smaller predators in check. In varying terrestrial and marine habitats and ecosystems in North America, mountain lions, grizzly bears, polar bears, American alligators, bald eagles, wolverines, gray wolves, and orcas are considered apex predators.

Bobcats and lynx are considered to be meso-predators, that is, medium-sized carnivores that occupy a mid-ranking level in a trophic system. Meso-predators are typically omnivorous or carnivorous animals that prey on smaller animals (e.g. rabbits, rodents) and regulate their populations. They also can be a source of food for larger predators. Raccoons, foxes, coyotes, skunks, and opossums are other examples of Colorado meso-predators. When apex predator populations decline, meso-predator populations can increase dramatically, a phenomenon called “meso-predator release.” This can harm ecosystem stability, as meso-predators may then prey too heavily on smaller animals that are important for plant pollination or seed dispersal.

Ecosystem services provided by Colorado wild cats. Mountain lions are considered ecological engineers because they help Colorado’s natural areas hum. The presence of top predators is perhaps the best single indicator of a healthy ecosystem, and the benefits lions and bobcats deliver include:

- Maintaining healthy prey populations.Mountain lions hunt coyotes, raccoons, rodents, wild pigs, and wild horses and burros. But their favored prey are deer and elk, the two most abundant ungulate species in Colorado, with each adult mountain lion consuming about 50 mule deer per year. Thus, they help regulate prey species abundance and herbivore pressure on the flora, preventing deforestation and erosion, and strengthening the fitness of surviving populations by culling weakened or otherwise vulnerable animals.

- Preventing disease introduction and spread in prey species.Mountain lions and bobcats prevent the spread and lessen infection and disease prevalence. For example, there is quality evidence that both mountain lions and wolves are “first responders” to Chronic Wasting Disease of deer and elk, a fatal potentially zoonotic transmissible encephalopathy of cervids that is currently prevalent in many Colorado mule deer and elk populations. Both mountain lions and wolves appear to preferentially target CWD-infected and symptomatic deer and elk. Some ecologists, such as renowned Princeton disease biologist Andrew Dobson, believe that CWD emerged in the late 1960s and spread across the U.S. in the past half-century precisely because of the absence of apex predators from most North American landscapes. Bobcats are also important in disease control. For example, they prey heavily on rodents that carry zoonotic Lyme bacterial disease and hantavirus.

- Promoting biodiversity. By controlling prey populations, apex predators indirectly create opportunities for other species. They enrich soil and plant communities: Nutrients from the remains of a mountain lion’s prey are released back into the environment, creating locations where animals like elk and deer more frequently forage. Seeds are dispersed in mountain lion and bobcat scat. Mountain lions prey on smaller predators such as coyotes, raccoons, and bobcats. This predation can help to control meso-predator populations, preventing them from overexploiting smaller prey species, such as rabbits, squirrels, and birds. Mountain lions and bobcats often leave uneaten portions of their prey, providing a valuable source of food for scavengers such as bears, ravens, and vultures. Mountain lion carrion provides food sources for hundreds of species.

Human ecosystem services provided by Colorado wild cats. How important are apex and meso-predators to human well-being? Multiple lines of evidence suggest that mountain lions and bobcats are economically and socially valuable to people. These are some of the benefits they provide to human society:

- Livestock and crop protection. Mountain lions keep deer numbers in check and keep deer moving, which reduces herd size and prevents overgrazing and loss of habitat (or crop) flora. This enables greater crop yields and more robust foraging by livestock to the benefit of farmers and ranchers.

- Reduced deer-vehicle collisions. Despite large apex predators being capable of threatening the safety of people, pets, and livestock, that safety cost is offset by broader benefits provided by their functional top-down control. Over-abundant populations of prey species in the absence of apex predators can negatively affect human well-being.

Though equipped with sharp teeth, claws, and incredible physical capabilities, mountain lions are far from the most dangerous wild animals to humans in North America. In the United States, this distinction goes to the mountain lion’s primary prey, deer. Around 2.1 million deer-vehicle collisions occur in the U.S. annually, causing more than $10 billion in economic losses, 59,000 human injuries, and 440 human deaths. These accidents are most frequent in the East, where mountain lions and wolves are absent, and deer have reached unnaturally high densities. On the other hand, lions cause virtually no automobile damage and the death toll on humans is about one a decade in the entire western United States.

Wildlife ecologist Sophie Gilbert and her University of Idaho colleagues estimated the economic value provided by mountain lions by reducing deer–vehicle collisions. First, the economic contributions of the nascent population of mountain lions in the Black Hills of South Dakota were calculated by comparing the number of deer-vehicle strikes before and after mountain lions re-established a breeding population. They found resident mountain lions reduced deer collisions by 9% (158 crashes), preventing $1.1 million in collision costs annually.

Gilbert’s team also predicted human benefits if mountain lions were re-established in the Eastern U.S., where mountain lions are currently absent. They predicted that mountain lions would reduce deer numbers by 22%, prevent 21,400 human injuries and 155 fatalities, and avert $2.13 billion in avoided costs in damages within 30 years of establishment, after which the deer density would stabilize again at a reduced (and healthier) number.

There are two proposed mechanisms as to how mountain lions (as well as wolves) prevent deer-vehicle collisions. First, mountain lions and wolves directly decrease deer population numbers by predation, with each mountain lion killing about 50 mule deer per year. Second, these apex predators induce fear in prey species, causing them to modify their behavior, keep moving, and avoid roads.

- Tourism. As a symbol of the wild and wilderness, mountain lions are a draw for tourists to Colorado, generating millions of dollars in revenue each year, especially in the state’s more rural reaches. They are a popular subject of photography, hiking, and wildlife viewing.

- Cultural, recreational, educational, and spiritual value. Mountain lions symbolize Colorado’s wild and rugged nature and are an important part of the state’s cultural identity. Mountain lions are revered by many Native American tribes as powerful and sacred animals.

Mountain lions and bobcats are primary actors in Colorado’s natural and human ecosystems, providing a cascade of benefits that shape the structure, function, and resilience of these landscapes. Their presence as apex and meso-predators contributes to the overall health and biodiversity of the environment, highlighting the importance of halting the cruel treatment and unwarranted killing of these much-revered creatures. Unfortunately, mountain lions are more prone to be persecuted for the problems they are perceived to present (e.g., occasional attacks on humans, livestock, and pets) than lauded for the ecosystem benefits that they provide.

The natural and human society ecosystem services of Colorado’s wild cats are here.

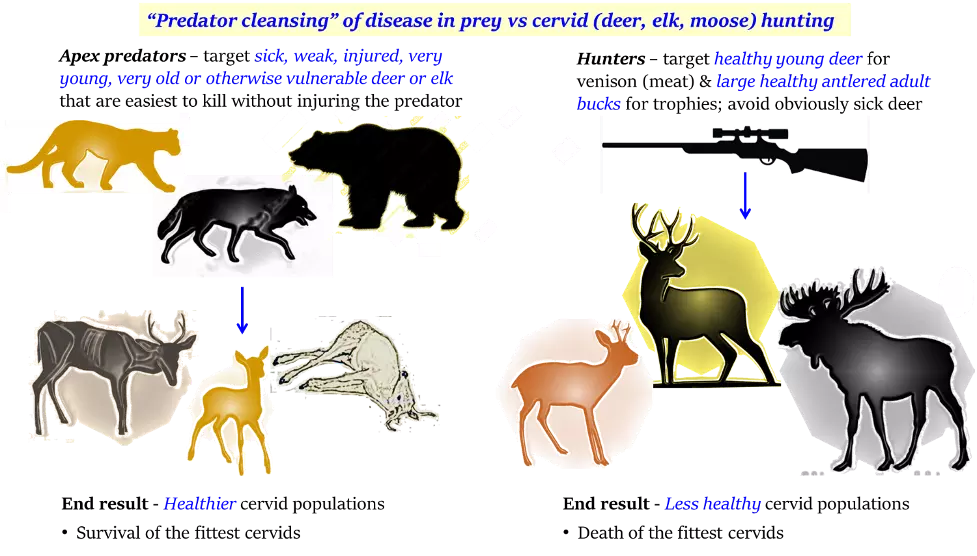

Below we can see how apex predators such as mountain lions can help to “cleanse” the prey population of disease and select for prey fitness. In general, human hunting is selective, too, but in a way that has an inverse effect — making deer and elk herds less healthy, as human hunters select the healthiest animals available to kill and thereby may create less eco-evolutionarily fit prey populations.

The dubious ethics of hunting and trapping Colorado’s wild cats:

fair chase, NAMWC, electronic calls, and trophy hunting

Ethical hunters follow guidelines derived from the harsh lessons of the past. For example, through the 1800s and into the early 1900s, unsustainable commercial and private hunting of fish and game was essentially unregulated in North America. At this time there were few laws or regulations governing the taking of game for food or sport.The result was predictable: extinction of some species (e.g., the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet), near extinction, and broad geographic extirpation of many species (e.g., the bison and wolf), and greatly reduced numbers of most hunter-targeted species (e.g., deer and elk).

For example, “deer jacking” (water-killing of deer) was a common practice in the Adirondacks and other parts of upstate New York from the late 18th century to the early 20th century. This method involved using packs of hounds, loud noises, and human chains to drive deer herds from forests towards frozen lakes, where they would be trapped and slaughtered (by shooting, clubbing, or throat cutting) on the ice, a ruthlessly efficient way to take large numbers of deer.

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (NAMWC) is a set of principles that guide wildlife management and conservation in the United States and Canada derived from tragic and cruel unsustainable practices such as “deer jacking.” The NAMWC is based on the idea that wildlife is a public trust resource that should be managed for the benefit of all citizens. The NAMWC also emphasizes the importance of science-based management and public participation in wildlife decision-making. (Note: The CATs campaign is an example of this NAMWC principle of public participation in wildlife management decisions in action). The core principles of the Model are elaborated upon in seven major tenets. Two of those seven are germane to this discussion.

2nd Tenet: Elimination of Markets for Game. Commercial hunting and the sale of wildlife is prohibited to ensure the sustainability of wildlife populations. The hunting and trapping of ~2,000 bobcats per year in Colorado and the commercial sale of their pelts to make luxury garments in Asia is an obvious violation of this tenet.

4th Tenet: Wildlife Should Only be Killed for a Legitimate Purpose. The killing of game must be done only for food, fur, self-defense, and the protection of property (including livestock and pets).

Up to 674 mountain lions will be killed for recreation and sport in Colorado this winter and spring. The primary purpose of the mountain lion hunt is to obtain apex predator body parts as trophies. This is also a self-evident breach of this NAMWC tenet.

Colorado law requires mountain lion hunters to harvest the large muscles (meat) from the upper legs (four quarters) and back muscles from all harvested mountain lions, presumably to address the 2nd tenet of the NAMWC.

The amount of mountain lion meat consumed is difficult to estimate, as there is no data available on how much of the harvested meat is consumed. Indeed, there is no tradition of eating cats in the United States, and the federal Animal Welfare Act forbids the trade in domesticated dogs or cats for meat — and wild cats are just smaller versions of the wild cats that inhabit Colorado.

Humans generally refrain from eating the meat of land mammal carnivores. It is axiomatic that very few mountain lion hunters in Colorado are interested in eating the animals they kill; that’s not the point of the hunt. Thus, the CPW policy of mandated use of mountain lion meat is an unenforceable requirement that is of very limited relevance or practical value. It may just prove to be a talking point for an agency and a special interest group that sanction inhumane and unsporting killing for no good reason. The provision is, at best, a public-relations ploy so that lion hunting retains sufficient support to persist and so that it is not viewed as violative of the North American Model and inconsistent with the norms that govern the utilization of other wildlife, such as deer and elk.

Most cultures, including many in America, have taboos against eating large apex predators. This is in part due to the zoonotic disease risk from wild carnivores if the meat is improperly cooked. For example, mountain lion meat can carry trichinellosis and toxoplasmosis, two parasitic infections found in raw muscle tissue that can cause serious human illness or even death. The meat of carnivores is often tough, stringy, and gamy, making it generally unpalatable. This is because carnivores have large amounts of connective tissue embedded in their muscle tissue and their meat diet can give their flesh a strong flavor.

The Fair Chase Principle is a hunting ethic that mandates hunters not use methods or technologies that give them an unfair advantage over the animals they are seeking and that the hunted animal has the opportunity to escape the hunter. The earliest known use of the term “Fair Chase” is in the fifth article of the Boone and Crockett Club’s constitution, adopted in February 1888.

The Boone and Crockett Club defines fair chase as the ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit of wild, native free-ranging North American big game animals. Fair chase does not give the hunter an improper advantage over the animals. Fair chase rules include balancing the hunter’s skills and equipment with the animal’s ability to escape, not using electronic calling, and not shooting in a fenced-in enclosure.

When in the field, the initial question for every fair chase hunter is whether the animal has a reasonable opportunity to elude the hunter. If the animal does not, the hunt can never be a “fair chase.” For example, a fair chase hunter does not shoot an animal hampered by deep snow or entangled in a barbed-wire fence.

The Pope and Young Club, a U.S.-based organization that promotes bowhunting, declares that a fair chase shall not use a bow and arrow with any electronic device to attract, locate, or pursue game or guide the hunter.

Listed below are the typical events in a Colorado mountain lion hunt, which most often costs several thousand dollars to outfit. Hunting mountain lions with hounds in Colorado is regulated, requires a valid hunting license, a mountain lion permit, and adherence to specific rules and guidelines set by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The process typically involves the following steps:

Obtaining permits and licenses. Hunters must purchase a valid hunting license and a mountain lion permit through CPW’s licensing system. They may also need to obtain additional permits depending on the specific area they intend to hunt.

- Identifying lion sign. Hunters scout potential hunting areas to locate fresh mountain lion tracks or other signs, such as scat or scrapes. Fresh snow can make tracking easier.

- Releasing hounds. Once a fresh track is found, hunters release a pack of trained hounds, typically houndsmen or lion dogs, to follow the lion’s scent. The hounds chase the lion, keeping it on the move and barking loudly to signal its location.

- Pursuing the lion. Hunters follow the hounds’ barks to track the lion’s progress. They may use GPS collars or radios to monitor the hounds’ movements.

- Treeing the lion. The lion, often exhausted from the chase, will typically either climb a tree or bay up in rocks to avoid the hounds.

- Making the kill. Once the lion is treed or bayed up, hunters approach and shoot the animals off of a tree limb using a firearm or archery equipment.

- Tagging and reporting. Hunters must tag the harvested lion and report the harvest to CPW within 48 hours.

Go here to view a 10-minute video of a mountain lion hunt in Western Colorado using hound dogs with GPS showing most of the above steps.

The use of GPS and radio-collared hound dogs violates the Fair Chase Principle. Furthermore, the mountain lion is, for all practical purposes, trapped and unable to escape once it is exhausted from the chase and treed, another violation of the Fair Chase Principle. Until late fall 2023, Colorado Parks and Wildlife permitted the use of electronic calls in certain wildlife management units to lure mountain lions, yet another breach of Fair Chase.

These principles are not abstractions but have animated voting behavior in the West. In fact, in five of five plebiscites, voters have favored the idea of protecting mountain lions from trophy hunting and hounding. California voters approved Prop 117 to ban lion hunting in 1990, and then handily rejected an attempt to overturn that ballot measure six years later. Oregonians passed a ban on hounding of lions in 1994, and then turned back a repeal effort on the ballot just two years later. And in Washington, voters passed a ban on hounding of lions in 1996 in a landslide vote of nearly two-to-one. The Colorado ballot measure will be the sixth statewide vote in the issue in the American West.

“The wildlife and its habitat cannot speak. So we must and we will.”

— President Theodore Roosevelt

Jim Keen, D.V.M., Ph.D., is director of veterinary sciences for the Center for a Humane Economy. He is a former research scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center and was on the faculty at the University of Nebraska School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. The second of this three-part series will be published soon.