The Economic and Ecological Value of Mountain Lions and Bobcats in the West: Part II

Do human hunters occupy the role of mountain lions as apex predators in Colorado?

- Dr. Jim Keen, DVM, Ph.D.

There has been long-running controversy over the trophy hunting of mountain lions in the West, and to a lesser degree, the same holds true for commercial trapping of bobcats.

Polling of the general population indicates that the majority hold the view that hunting and trapping of these apex and meso-predators are inhumane, unsporting, and unnecessary, while others believe that hunting is a necessary tool for managing mountain lion and bobcat populations and constitutes an acceptable use of wildlife.

The issue has been put to the test multiple times with up-or-down votes on the issue, and in every circumstance, voters have sided with the idea of imposing stricter limits on hunting lions. Voters supported a total ban on trophy hunting of lions in California twice (1990 and 1996) and outlawed hounding in Oregon twice (1994 and 1996) and in Washington (1996).

We know that mountain lions and bobcats provide many natural ecological and human societal benefits (see Part I of this series). According to some proponents, when humans hunt apex predators, they functionally replace these predators. So, the question arises: Can humans replace the ecological roles of apex predators like mountain lions?

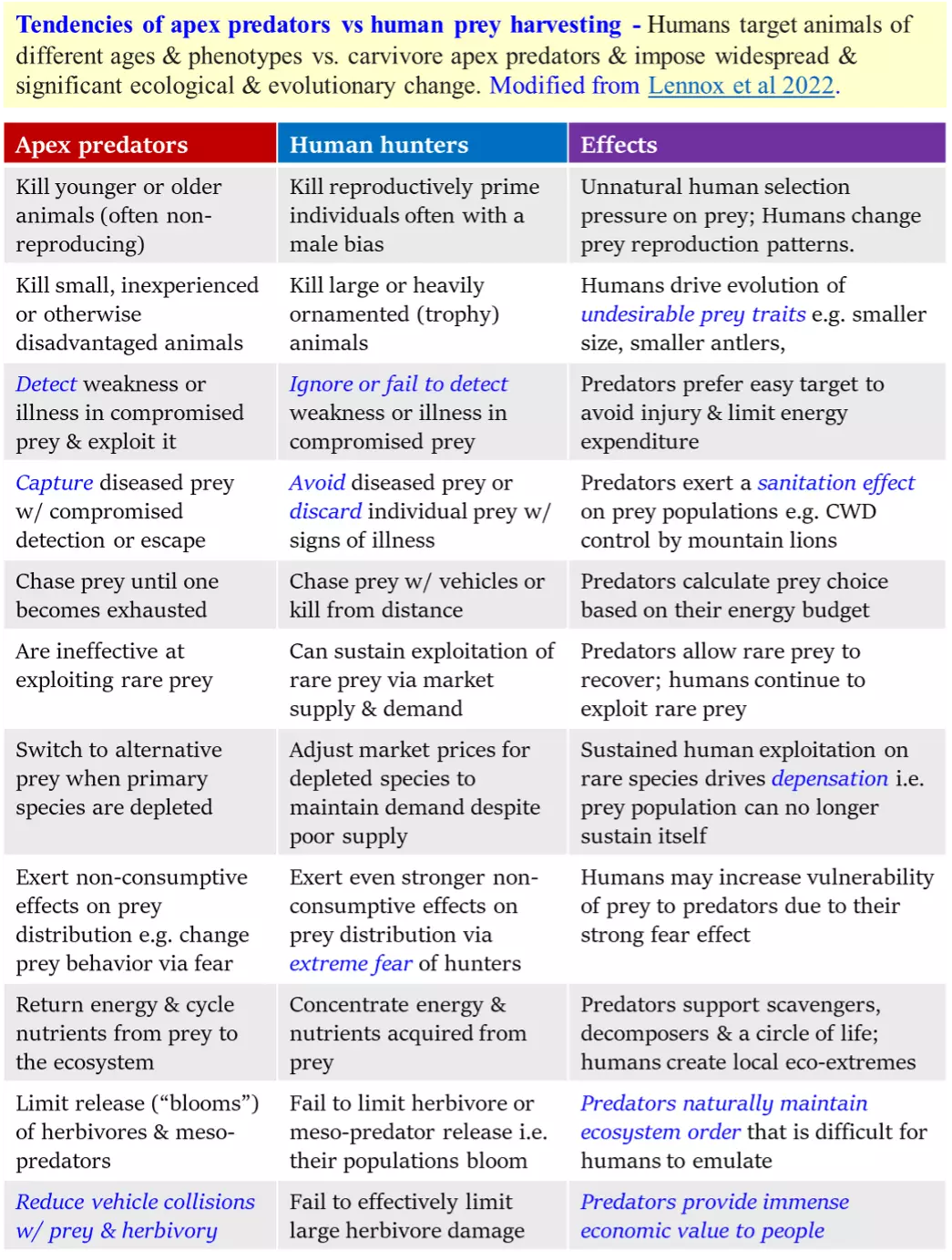

Ecologist RJ Lennox and colleagues (2022) tried to address this question. They compared how human hunters and apex predators affected ecosystem structure and function. The underlying idea was to assess whether humans can generate or simulate the ecosystem benefits of apex carnivores. They defined the five major effects of predators as:

- Guiding the evolution of their prey

- Managing disease outbreaks in prey

- Regulating the distribution of prey

- Controlling the flow of carbon and nutrients in the food web

- Effects on human health and safety.

Table 1 summarizes their findings.

Mountain lions vs. human hunters. Mountain lions and humans are both successful apex predators, but they approach prey selection and hunting differently. The different prey preferences and carcass consumption habits of human hunters and mountain lions result in dramatically different effects on the health of deer populations.

- Mountain lions are primarily opportunistic hunters who prey on whatever is available and easiest to catch and kill, which means their diet varies depending on the time of year, location, and prey availability. They typically target ungulates (e.g., deer, elk, and bighorn sheep), but they also will eat smaller animals like rabbits, rodents, and birds. Mountain lions are ambush predators relying on stealth and surprise to take down prey. They will patiently stalk their quarry and then launch a quick attack, using their quickness, leaping ability, and sharp claws and teeth to kill.

- Human hunters are more selective and more flexible in their prey choice with specific preferences based on taste, trophy value (e.g., large body size, large antlers), and hunting regulations. With a wider range of low-risk hunting methods at their disposal (firearms, archery, and traps), humans can target prey from a distance or in difficult terrain.

- Human hunters typically target larger adult males while mountain lions prefer smaller younger females. This prey selection difference is due to the different hunting strategies and energy requirements of the two apex predators. Human hunters use firearms or archery to kill their prey from a distance at low energy cost, permitting the targeting of larger, stronger animals without putting themselves at risk. Mountain lions are solitary predators relying on stealth and ambush to capture their prey so they are more likely to target smaller, weaker animals who are easier to subdue without causing serious injury.

- Human hunters and mountain lions have different carcass consumption habits due to differing nutritional needs. Humans typically consume a portion of the cervids they kill. Mountain lions often consume the entire carcass. Humans have a diverse diet and can obtain necessary nutrients from many sources. Mountain lions are obligate carnivores relying heavily on deer and elk.

- Human hunters often target deer in good physical condition, as these animals are more likely to produce high-quality meat or higher trophy status. Mountain lions are opportunistic predators and will prey on any deer whom they encounter, regardless of its condition or location. However, they are more likely to target deer who are young, weak, or sick, as these animals are easier to catch and kill.

Human hunters cannot replace apex predators. Lennox and colleagues concluded that there is little evidence that human hunters can replace the beneficial services that wild predators like wolves and mountain lions provide to human society and to the environment. This is likely because humans and wild predators are targeting and removing different individuals from the prey population and, over time, driving very different outcomes on the prey population and the larger ecosystem.

The contrasts between humans and apex carnivore predators suggest consistently different patterns of prey selection with implications for predator-prey evolution, disease dynamics, prey distributions, carbon and nutrient cycles, and human societies. Human hunters drive an undesirable evolution by selecting large, fit, and dominant prey phenotypes out of the population. Thus, human hunters select for evolutionarily less fit cervid prey populations: slower, smaller, weaker, more disease-prone, less ornamented males. Mountain-lion hunting selects deer with high ecological fitness to their habitat.

Lennox and colleagues propose a better accounting of the value predators provide to improve conservation efforts, guide better wildlife management, and inspire human harvesting strategies that better imitate the positive impacts of apex predators.

Note: Just as human hunters are likely driving decreased fitness in the prey deer and elk populations, the sport and trophy hunting of predators like mountain lions in Colorado is almost certainly making predator populations less fit.

Since hunting is a major cause of death of both mountain lions and their primary cervid prey, human hunters are likely driving the increase of undesirable traits in both predator and prey via non-adaptive harvest-induced evolution.

All predators are agents of natural selection who shape prey phenotypes, or characteristics, over time. The arms race between predators and prey is a major driver of prey phenotypes. Apex predators like mountain lions tend to impose selection against prey phenotypes that are slow, weak, disease-prone, or otherwise vulnerable to attack as dictated by the predator’s skills. Human hunters have escaped most of these constraints that drive prey species evolution because they exploit prey in fundamentally different ways by using tools, such as ammunition, firearms, GPS technology, electronic lures, and game cameras. Theoretical modeling suggests that predation by humans can lead to morphological (e.g., smaller size-at-age, growth rates, ornament size), life history (e.g., reproduction at younger ages and sizes), and behavioral changes to prey populations in ways that are different from outcomes from apex predator hunting.

The loss of apex predators from persecution, hunting, and habitat conversion. The hyper-exploitation of lions — with trophy hunters killing 500 lions and houndsmen changing hundreds or thousands more and causing massive energy expenditures, animal fights, and stress — inevitably has major consequences on prey populations by decreasing selective pressure on them, disrupting the delicate balance of ecosystems and leading to a cascade of negative effects.

Halting trophy hunting of lions is not just about sparing individual lions from the effect of cruel chases and killing, but also about safeguarding the health and resilience of the larger community of native species in Colorado. The decline of top carnivores has released (i.e., caused their populations to bloom) large herbivore populations and meso-predators around the world, incurring socio-economic costs such as increased animal–vehicle collisions, elevated zoonotic disease risk, and loss of biodiversity. Human hunting of deer does not resolve these ecological problems. Particularly in the East, where wolves and lions are not absent, deer hunting has failed to control overabundant deer, and deer–vehicle collisions continue to rise at alarming rates.

Because mountain lions occur in naturally low population densities, even in optimal habitats (estimates are about 2 mountain lions per 100 square km), additional sources of unnecessary and unnatural mortality, such as trophy hunting, can alter and destabilize population dynamics over large areas.

The most common causes of mortality of mountain lions and bobcats are shown below. Note that human activities (vehicle collisions, lethal conflicts with people or their property, habitat loss and fragmentation, hunting and trapping) are the major drivers of both bobcat and mountain lion deaths.

The major causes of mountain lion mortality in Colorado are:

- Human-caused mortality. This is the leading cause of mountain lion mortality in Colorado. It includes trophy hunting, attacks by packs of dogs, vehicle collisions, and depredation or public safety control (killing mountain lions who have attacked people, livestock, or pets).

- Disease. Mountain lions can contract several diseases, including viral, bacterial, and parasitic diseases. Disease weakens mountain lions and makes them more susceptible to other threats.

- Injury. Mountain lions can be injured in many ways, including fighting with other mountain lions over mates, prey, or territory, falling from cliffs, and being hit by vehicles. These injuries can be fatal.

- Starvation. Mountain lions can starve to death if they are unable to find enough food or are injured and unable to hunt. This can also happen if their prey populations are declining or if they are displaced from their habitat.

The primary causes of bobcat mortality in Colorado include:

- Vehicle-related collisions. Bobcats are frequently struck and killed by vehicles, particularly on highways and roads that bisect their habitats.

- Predation. Bobcats are preyed upon by still larger predators such as coyotes, mountain lions, and wolves.

- Disease. Bobcats are susceptible to a variety of diseases, including rabies, feline distemper, and toxoplasmosis. These diseases can weaken bobcats and make them more vulnerable to other threats.

- Trapping and hunting. Bobcats are hunted and trapped for their winter fur pelts or nuisance control purposes. Trapping and hunting cause direct mortality, or indirectly by injuring or stressing bobcats, making them more susceptible to other threats.

- Habitat loss and fragmentation. As human development encroaches on bobcat habitat, these wild cats are more likely to come into conflict with humans, their pets, and their livestock. Additionally, habitat fragmentation makes it more difficult for bobcats to find food, shelter, and mates.

Risk Factors Posed by Mountain Lions and Bobcats in Colorado

Around the world, apex predators are declining due to habitat loss, direct hunting, or persecution. Significant roadblocks impede large carnivore conservation. Large carnivores are harassed worldwide. Much of their natural habitat is gone or fragmented. They sometimes kill owned or coveted animals, including pets and livestock and hunting ungulates. Traditional old-school thinkers celebrate the elimination of top predators for reducing predation pressure on prey populations that can release greater yields for human taking.

Until 1965, the State of Colorado sought to exterminate mountain lions, offering bounties for hides. Today’s long and permissive trophy hunting seasons, including the use of ruthless and unsporting methods, are a vestige of those long-standing anti-predator sentiments, driven by the desires of some ranchers, trophy hunters, and the commercial guiding industry who typically charge large fees for a guaranteed kill of a lion by their clients.

Predators are more prone to be persecuted for perceived threats or nuisances rather than praised for the ecosystem services they provide. Human-predator conflict commonly arises from a belief that the resources required by predators to carry out their beneficial effects exceed the value they provide.

Risk Factors Posed by Mountain Lions and Bobcats in Colorado

- Predation on livestock. Mountain lions and bobcats are opportunistic predators and may prey on livestock, such as sheep, goats, and cattle, causing economic losses for ranchers and farmers. The majority of mountain lion removals in Colorado are related to livestock depredation, meaning that the mountain lion had been confirmed to have killed or injured livestock, and removal was deemed necessary to protect livestock owners.

Nationwide, based on USDA Wildlife Services reports, the average annual number of livestock losses attributed to mountain lions is around 450-500. This suggests a possible total of 2,250-2,500 livestock attacks over the past five years. From 2000 to 2021, USDA Wildlife Services killed, on average, 340 mountain lions each year in the United States. These kills were in addition to those permitted by various state wildlife agencies. That number does not include depredation kills by personnel from state fish and wildlife and agriculture departments.

- Predation on pets. Mountain lions are known to prey on pets, such as dogs and cats. This can be a devastating loss for pet owners and can create tension between mountain lions and humans. Pets left outside at night are at risk in Colorado in mountain lion habitats. There are no readily available statistics on mountain lion attacks on pets in Colorado, but at least one lion did kill dozens of pets in Nederland in 2023 before he was killed

Colorado Parks and Wildlife conducted an extensive study between 2007 and 2015 in which it captured and collared 102 mountain lions in five counties with resident mountain lion populations. The study found that 39% of collared mountain lions consumed domestic animals such as dogs, cats, and hobby livestock.

- Human safety. Mountain lion attacks on humans are rare, in part because these apex predators do not normally perceive two-legged animals as prey species. Mountain lions are also generally fearful of humans. However, mountain lion encounters can be dangerous for children and solo hikers.

In the United States, between 1890 and 2022, there were 126 attacks on people by mountain lions, causing 27 fatalities, according to data compiled by the Mountain Lion Foundation and other sources. This represents an average of about 1.3 mountain lion attacks on humans per year and two fatalities every decade

Between 1990 and 2023, there were 25 confirmed mountain lion attacks on humans in Colorado, resulting in three fatalities. In the most recent attack in March of 2023, an 11-year-old girl was attacked by a mountain lion while walking home from school in El Paso County. The girl was able to fight off the lion and sustained only minor injuries.

As a relative risk reference point, according to DogsBite.org, there have been 34 fatal dog attacks in Colorado since 1990. Pit bull-type dogs were responsible for 22 of these attacks, followed by Rottweilers, with four attacks. According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, there were 15,645 reported dog bites in Colorado between 1990 and 2021. Statistically speaking, then, the risk of attack and death from domestic dogs is of a different order of magnitude than lion attacks. The policy response to the dog attacks is often to kill the offending animal, but there are no calls for random or mass killing of dogs or vengeful acts against non-offenders. .

- CPW will remove (trap and relocate or sometimes euthanize) mountain lions who pose a direct threat to human safety. This could include instances where a mountain lion has attacked someone or is exhibiting aggressive behavior toward humans.

- According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife 2022 reporting, there were 787 mountain lion incident reports which include alleged or supposed sightings, aggressive behavior, and property damage. The state allowed wildlife officials and property owners (and deemed justified) to kill 20 lions, with most of those kills on the Western Slope

- Habitat loss and fragmentation. Mountain lions are losing habitat due to human development, which can lead to increased conflicts with humans. Habitat fragmentation also makes it more difficult for mountain lions to find prey and mates, which can further strain and stress lion populations.

- Disease transmission. Mountain lions can transmit diseases to humans and domestic animals, such as rabies and tularemia. While the risk of disease transmission is extremely low, it is still a concern for some people, especially hunters.

- Public perception. Mountain lions are sometimes perceived as dangerous or threatening animals, which can lead to fear and hostility towards them. This can make it difficult to manage mountain lion populations effectively and can also lead to unnecessary persecution of these animals.

Public education, responsible recreation, and effective management practices are all important for minimizing conflicts with mountain lions (or bobcats) and ensuring that these majestic animals can continue to thrive in Colorado. Banning trophy hunting of mountain lions will help to ensure their long-term survival and lessen the risk of human-mountain lion conflicts.

Bottom Line: Will Trophy and Sport Hunting of Mountain Lions Improve the Safety of People, Pets, and Livestock?

Colorado is one of 14 states that allow mountain lion hunting. Others are Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. About 500 adult mountain lions are killed each year in Colorado, out of an adult population of an estimated 3,000 to 7,000 animals. According to the Mountain Lion Foundation (MLF), the best available evidence indicates that trophy hunting of mountain lions will not decrease public safety or livestock and pet depredation risk from mountain lions and may increase human conflict risk.

According to the MLF, an overwhelming number of studies demonstrate that trophy hunting of mountain lions not only does not increase the public’s safety, but it also does not reduce depredation on livestock or other domestic animals and appears to be responsible for the increase in human/lion conflicts in regions where lion mortality is excessive.

The claim that sport and trophy hunting is a necessary and effective strategy for reducing mountain lion attacks on people, pets, and livestock remains widespread in the mainstream media, the hunting community, and the popular hunting literature. According to the MLF, “While some state wildlife agencies, such as in California and Wyoming, state that sport hunting cannot be expected to increase public safety, other state agencies have claimed the opposite, apparently to garner public support for sport hunting.”

Conclusion

A ban on mountain lion and bobcat hunting and trapping would benefit Colorado economically, ecologically, and ethically.

Mountain lion hunters as well as bobcat hunters and trappers drain Colorado’s natural resources solely for personal benefit (trophies) or commercial profit (e.g., mountain lion hound outfitters, bobcat pelt sales).

Perhaps counterintuitively, big cat hunting and trapping bans in Colorado would likely improve public safety and reduce livestock and pet depredations by maintaining the stability of local mountain lion populations and families of females raising cubs. Widespread indiscriminate mountain lion hunting does not appear to be an effective preventative and remedial method for reducing predator complaints and livestock depredations.

Colorado is large enough and the people are compassionate and wise enough for mountain lions and bobcats to co-exist with humans without unnecessary and destructive trophy hunting and trapping of these beautiful and beneficial wild cats. California’s experience proves that, given that it has the lowest per capita rate of lion incidents with people in the nation, and the state has outlawed trophy hunting for more than five decades.

In Part I in this series of blogs relating to the purposes of the Cats Aren’t Trophies (CATs) campaign, Dr. Keen described the ecological and societal benefits of maintaining healthy, wild, free-living, and unmolested mountain lions and bobcat populations in Colorado, and how current Colorado Parks and Wildlife regulations on hunting and trapping of these wild cats are unethical under normal hunting standards of conduct. You can read it here

In Part III, Dr. Keen will summarize the experimental and observational evidence that apex predators, especially mountain lions and grey wolves, offer the best defense against Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) of deer, elk, and moose. CWD is highly prevalent in Colorado’s deer and elk populations. This fatal rapidly expanding neurological disease of cervids is the greatest ongoing and future threat to North American deer and elk populations.