Science

10 science-backed reasons for Colorado to support CATs

because studies show trophy kills and trapping will:

Trophy hunting kills females with dependent juveniles and young kittens, who then face a 4% chance of surviving. Orphans mainly die of starvation. Just seeing a female mountain lion alone does not mean that she does not have dependent kittens. Dependent young remain with their mothers for up to 18 months learning crucial survival skills. A female will have dependent young during up to 83% or two-thirds of her lifetime. Colorado does not require trophy hunters to check to see if a female is lactating before shooting her and about 41% of mountain lions (from 2019 to 2022) killed by hunters each year are female.

Bobcat trappers set and bait cages randomly day and night throughout the state and without “bag” limits. There is nothing to prevent mothers with dependent young from being trapped and killed, leaving orphans behind.

Both bobcats and mountain lions can and do breed any time of year.

“Whenever you have trophy hunting mountain lions, you will have created orphans.”

— Rick Hopkins, Ph.D, a nationally recognized wildlife ecologist, who has dedicated more than 45 years to the study of large mammalian carnivores.

More resources:

- Read this article by a Colorado hunter on ethics (Colorado Newsline)

- Read this article on the death of hunting ethics when it comes to predator hunting (Todd Wilkinson, Mountain Journal)

- Read Colorado’s Citizen Petition to end bobcat trapping

- Read what a Colorado hunter said to CPW to try and end bobcat trapping

- Read about how Lynx mortalities are related to being shot and trapped

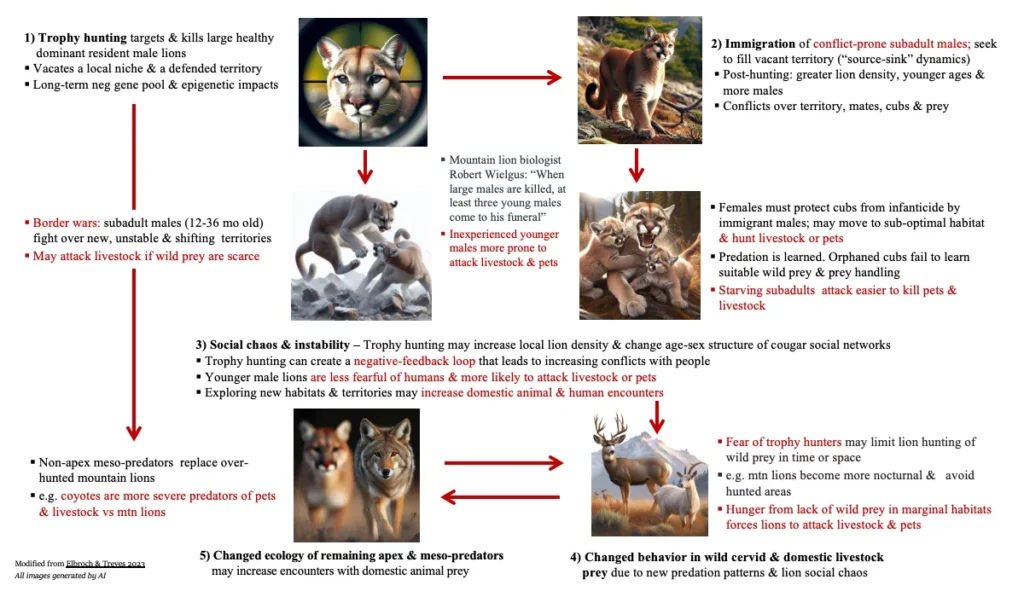

Trophy hunting targets established, mature mountain lions who are coexisting peacefully with humans, appropriately hunting deer and elk, and are not involved in conflict, which is why they have lived for so long. Trophy hunting disrupts lion social structure and opens new territory for multiple juveniles who are scientifically proven to be more likely the cause of potential future conflicts, specifically complaints and negative encounters with livestock and with a high degree of confidence, pets. Science dating back to 1971, and the (Stanley) Cain Report, university research by John Laundré, and Robert Wielgus and wildlife agency research by Maurice Hornocker, and field studies by Harley Shaw and others all say the same thing: killing of random predators (trophy hunting) taking out established mature lions who are being appropriate, living naturally, preying on deer and elk, and peacefully coexisting for years to maturity does not prevent predation on livestock or pets, and it will backfire, causing increased human-lion conflict as well as complaints, where none existed before.

See “Effects of remedial sport hunting on cougar complaints and livestock depredations”. (Plos One)

“When you kill one older dominant male (cougar), three younger guys come to the funeral.”

— Robert Wielgus, Ph.D. a retired Associate Professor and Director of the Large Carnivore Conservation Lab at Washington State University. He is an internationally recognized expert in the study of large carnivores and has published over 30 peer reviewed scientific papers.

It’s important to note that trophy hunting and trapping wild cats in Colorado is divorced from professional handling of precise yet rare human-lion conflict, and we have separate and distinct, and well-funded state and federal programs to prevent and effectively address individual cases of conflict with ranchers in Colorado.

- Read USDA Resolves Wildlife Conflicts in Colorado

- Read Wildlife Services-Colorado (offices in Lakewood)

This graf shows about 60 mountain lions are killed in Colorado by state and federal agencies for conflict each year from 2020 to 2022.

Trophy hunts target the largest prizes for a photo, the head and a hide. In Colorado, statewide tooth age data show that more juvenile and subadult mountain lions are being killed by trophy hunters, which is indicative of high hunting pressure causing a decline in population age.

It has been long-understood that sport-hunting lowers the average age of wildlife populations. In mountain lions, this results in a disproportionately younger population that has considerably less experience in securing food (i.e., predation has a strong learned component). Less experienced individuals often lead to heightened conflict with human interest: In areas where there is trophy hunting, the average age of the animals in the population declines, because the probability of older and larger individuals surviving declines with each successive hunting season. By definition, trophy hunters prize the larger, more mature animals. In Colorado, recent data shows we are seeing more juveniles or subadults being killed by trophy hunters, which is indicative of high hunting pressure causing a decline in population age. Trophy hunters are running out of older, mature males to target and kill.

Add to this, when you have a lot of females killed (40% average from 2019 to 2022) this also suggests there is high hunting pressure in the state. Also, the number of days it takes a mountain lion hunter to kill a lion has been increasing (1,590 days in 2020-2021 to 1,821 in 2021-2022). ). This is suggestive that there is more hunting pressure on the lion population. As mature adults are depleted, hunters spend more time searching for one. Without hunting pressure, lions live longer, and are less likely to engage in conflict.

Trophy hunting will lead to long term negative impacts to the population, given the many existing threats to wild cats today, including climate change, disease, vehicle deaths and poisoning.

Trophy hunting and trapping are not conserving or creating healthy populations of wild cats in Colorado. Researchers for the Hornocker Wildlife Research Institute writes, “Our research (10 years) in New Mexico indicates that mountain lion populations will stabilize at a level depending on available habitat and food resources.” In California where mountain lions haven’t been hunted for a half-century and bobcats for 3 years, and in states where bobcats are not trapped, such as Connecticut and New Jersey overpopulation is not an issue.

When trophy hunters say they are “conserving” or “managing” mountain lions, what they really mean is they are not overhunting them. But if you remove trophy hunting and trapping wild cats altogether, then there is no longer a need to manage trophy hunters, and it removes the top mortality risk to all wild cats in Colorado.

Without trophy hunts, Colorado can and will still be able to continue to manage individual mountain lions who may find themselves getting into trouble. This is completely separate from trophy hunting.

“Sport hunting is not an effective tool for anything other than providing an opportunity for sport hunting,”

-— the late Professor John Laundré of Western Oregon University, author of Phantoms of the Prairie: Return of Cougars to the Midwest

Although it is illegal to harm or kill lynx, they have been mistaken for a bobcat and have been caught, injured or killed in bobcat traps.

Canada lynx disappeared due to trapping for their fur, poisoning and decreased habitat, but were reintroduced in the 1990’s by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Although it is illegal to harm or kill lynx, they may be mistaken for a bobcat or get caught, injured or killed in bobcat traps. Trapping continues to be a significant cause of mortality of Canada lynx: In areas where trapping of Canada lynxes is permitted, mortality rates have been noted to range from 50% to 90%, and in areas where Canada lynxes are protected, mortality rates have been noted to range from 0% to 27%, increasing when mothers with dependent young are trapped. Lynx are attracted to bait set for bobcats, and can be harmed, injured or killed when caught in traps.

There are articles of lawsuits and incidents in states with lynx in which lynx are caught in traps set for other species:

Idaho: Lynx caught in live trap.

Montana: Between 1998-2008, at least 15 lynx were inadvertently caught in Montana traplines set for other species.

CPW data shows a Colorado lynx traveled to Canada and was killed in a trapping line neck snare. There was another lynx who was shot and killed by a person who thought it was a bobcat.

Read about how Lynx mortalities are related to being shot and trapped

Thousands of bobcat traps are set indiscriminately and unattended on public lands every year and wild animals including bald eagles and domestic pets can and have been caught, injured, and killed due to exposure to the elements or while struggling to escape.

Trophy hunting does not reduce the risk of being attacked, which is extremely rare. California, with 39.24 million people, known for recreating outdoors year-round, has not allowed trophy hunting mountain lions for a half-century. Leading mountain lion biologist the late John Laundre at Western Oregon University compared 10 western states with cougars, California had the third lowest rate of per-capita attacks on people, with 0.4 attacks per million persons. With 5.8 million people living in Colorado, and 92% of us recreating outside each year, especially in our forests and natural spaces, it’s not at all surprising to know that the risk of being attacked by a mountain lion is incredibly low. You are more likely to be struck by lightning on your birthday than attacked by a mountain lion.

“The risk of a cougar attack — on people or domestic animals — is extremely low, and almost zero with pragmatic precautions. Fewer than two dozen people have been killed by cougars in North America in the past 100 years.”

– Mark Elbroch, director of the puma program at Panthera, a nonprofit organization focused on protecting wild cats and the ecosystems they inhabit.

If public safety is truly a concern, wild animals should be far down on the list of what we should fear. For example, automobiles caused 745 deaths in 2022 alone in Colorado. Meanwhile, mountain lions have killed just three people since 1990, in a state with a population of nearly 6 million.

Consider again: 92% of Colorado residents participate in outdoor recreation each year. Rock climbing, hiking, skiing backcountry terrain, mountain biking, hunting and jogging on trails are all part of the Colorado lifestyle, where mountain lions thrive in these spaces, too.

Think about that. If lions were out to get us, we would have many more encounters and deaths. The fact is, you actually have a greater risk just driving and walking to a trailhead, than you do being touched by a mountain lion in Colorado.

In 2022 alone, there have been nine deaths from climbing 14ers; According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the death rate for rock climbing in Colorado is 12.5 per 100,000 population. This rate is higher than the national average of 10.4 per 100,000 population. According to records, more than 70 people have died climbing Longs Peak.

In 2022, Colorado recorded 46,751 deaths, with 15% from accidental drug overdoses. Most other major causes of death were illness, traffic accidents. Zero were from mountain lions.

Trophy hunting and trapping wild cats does nothing to protect our domestic animals, including pets from predation. See Perspective: Why might removing carnivores maintain or increase risks for domestic animals? (Biological Conservation, 2023). Trophy hunting can increase risk by leaving orphans and lowering population ages to younger animals with lesser hunting skills, who are more likely to get into conflict by preying on pets that go unprotected.

See heightened risk to livestock from trophy hunting: No. 2

“The wheels would not fall off the bus if Colorado stopped sport hunting mountain lions today. Recreational hunting of mountain lions does nothing to protect livestock, human or pet safety or produce more elk and deer for hunters to shoot.”

– Rick Hopkins, Ph.D, Puma Population Ecologist for four decades

Several studies dating back to 1971 looked into whether increasing trophy hunts of mountain lions could increase deer populations. It doesn’t work. See Efficacy of Killing Large Carnivores to Enhance Moose Harvests: New Insights from a Long-Term View (2022) and Demographic response of mule deer to experimental reduction of coyotes and mountain lions in southeastern Idaho (2011).

“Sport hunting [of mountain lions] to benefit wild ungulates [aka elk and deer] populations is not supported by the scientific literature…” — Colorado’s Division of Wildlife biologists in Cougar Management Guidelines

Trophy hunting of wild cats perpetuates the myth that mountain lions are looking to harm humans, followed by the idea that we somehow need to kill animals to feel safe, which is unsupported by science, statistics and lion ethology.

Just like any large carnivore, mountain lions deserve our healthy respect, but research shows that mountain lions highly prefer not to be around humans, they do not see us as food, or competition, and are not aggressive toward humans by nature. In this regard they are very different from African lions and tigers.

Researchers who approached mountain lions several hundred times at more than 60 den sites, with females and young, report only three instances of being charged by a mountain lion and in all three instances they were trying to encourage a female to leave the den so they could mark the kittens. In all cases the female broke off the charge or backed away then quickly left the area.

- Watch The Secret Life of Mountain Lions, a 6-minute video narrated by Chris Morgan (PBS, BBC, National Geographic). This video contains extraordinary footage captured with motion-triggered cameras from Panthera’s Teton Cougar Project. Once feared and hunted by humans, new footage captured by motion-triggered cameras shows a mountain lion family and the animals’ unknown social bonds. We also learn about how hard it can be to be a mountain lion, as they face an increasing loss of habitat, harsh winters, trophy hunters and even predators. One cub is lost to an attack by a pack of wolves and another to trophy hunting.

- Read more on how a young mountain lion used research equipment as ‘fun new toy’ in New Mexico’s desert, Yahoo News, June 2023

- Watch this rare video captured by the National Park Service, who caught these mountain lion kittens trying to roar but they ended up purring!

- See how this Coloradan captured footage of a mountain lion playing with a home-built swing.

- Watch three kittens play in a Larkspur backyard. “Kittens learn hunting skills through play and exploration, and by watching their mother.” (CPW NE Region post)

- Watch this footage captured by a Coloradan in Palmer Lake of a mother and her kittens.

- See Bandelier National Monument Facebook post May 2023.

- Read more on how a young mountain lion used research equipment as ‘fun new toy’ in New Mexico’s desert, Yahoo News, June 2023

- Northern California Homeowner Stunned to Find Mountain Lion Playing with Dog in Yard (msn.com)

- Watch a mountain lion in this video swimming across the Eagle River in early August.

“Most people don’t see them,” said Rachael Gonzalez, a public information officer with Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “Obviously with technology, we see them more because they’re captured on Ring Doorbells and stuff like that. But the reality is mountain lions, they don’t want to be seen.”

— from the article about this video

An exciting body of research from our country’s leading mountain lion ecologists shows that mountain lions bring vast benefits as apex predators and ecosystem engineers.

Today we know that mountain lions hold vast intrinsic value alive, serving a vital role within our Colorado wildlands ecosystem and are documented to support 500 species.

Today, we have the benefit of new independent science from the world’s top lion ecologists, clearly showing that wild cats play a critical role in building and sustaining healthy ecosystems, and notably at a time when biodiversity losses worldwide are at extreme highs due to human activities, including overhunting, pollution, and destruction and fragmentation of habitat.

Watch the 60-second video showing 543 distinct interactions between mountain lions with other living species. Mountain lion kills leave carrion for multiple species, increasing biodiversity.

- Read This Cat Holds Ecosystems Together | Psychology Today (Psychology Today, 2022)

- Read Pumas Puma concolor as ecological brokers: a review of their biotic relationships, Elbroch et al (Mammal Review, January 2022)

- Read Pumas engineer their environment providing habitat for other species, John Cannon (Mongabay)

- Read Pumas as ecosystem engineers: ungulate carcasses support beetle assemblages in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. (Elbroch et al Oecologia)

- Read Mountain Lions as Ecosystem Engineers, (Animal Tracking, Dr. Mark Elbroch)

- Read Want to save the planet? Focus on wild cats. (Dr. John Goodrich) Washington Post, December 2022.

- Read The ecology of human-caused mortality for a protected large carnivore (PNAS March 2023)

Read Mountain Lions Are Keystone Providers for Birds! (Hillary Shughart, Public Radio, May 2023)

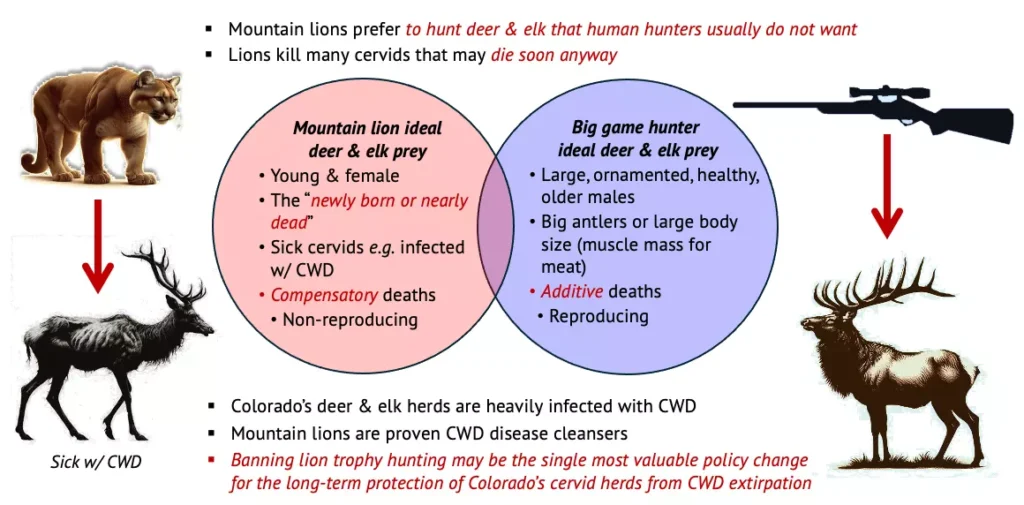

We also know that mountain lions are highly valuable in Colorado’s fight against the spread of the highly infectious and lethal Chronic Wasting Disease. CWD has been detected in 40 of our 54 deer herds and our wildlife agency says “controlling CWD is “critical for the long-term health of our herds.” A Colorado study shows that mountain lions are much more efficient than humans at lessening both the transmission and prevalence of CWD in our wild places. CWD has also been detected in nearly half of our elk herds and moose. Infectious disease experts warn that CWD could affect people as it mutates and adapts.

CWD is a horrific neurological disease with animals suffering slow deterioration of the brain before death. The fact that mountain lions could be saving thousands of deer, elk and moose from this fate is something all Coloradans — including deer and elk hunters — can appreciate.

“Unlike us, the lions sense that while a deer might look vigorous and alert, it may actually be a ticking time bomb. That’s one of the many weird things about this disease. It isn’t like viral or bacterial illnesses. The infection can sit in a herd for years, crawling from animal to animal, before people notice anything is wrong.”

— Rae Ellen Bichell is a regional radio reporter with the Mountain West News Bureau. She’s based at KUNC in northern Colorado. She frequently covers science and health.

- Read “The disease devastating deer herds may also threaten human health” (High Country News)

- Read “Scientists are exploring the origins of chronic wasting disease before it becomes truly catastrophic” (High Country News)

- Read “ Faced with chronic wasting disease, what’s a hunting family to do? Hunters are critical of game management, but the spread of CWD means some may put down the rifle” (High Country News)

- Read “Chronic wasting disease (CWD) kills every deer, elk and moose it infects by slowly boring holes in their brains”

“Our hunt region has one of the highest-known prevalence rates on the continent in deer.”

— from Chronic wasting disease (CWD) kills every deer, elk and moose it infects by slowly boring holes in their brains”

See how mountain lions are keeping our deer herd healthy in our CATs report on Chronic Wasting Disease & the Predator Cleansing Hypothesis by infectious disease specialist Dr. Jim Keen D.V.M, Ph.D. here. Dr. Keen served on the faculty of the University of Nebraska College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and worked for the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center (USDA) in Clay Center, Neb. for nearly two decades.

Researchers also have found that by modulating deer populations, mountain lions prevented overgrazing near fragile riparian systems. Coloradans should be asking tough questions, such as why our state remains focused on a singular trophy hunting and trapping program, and not engaged in the science of infectious disease, climate and wildlife, particularly of mountain lions as a key solution.

Big Cats as Nature’s Check Against Disease

A summary of theoretical, empirical, and experimental evidence supporting predator cleansing of CWD in deer and elk herds by mountain lions and wolves.

by Jim Keen, D.V.M., Ph.D.

A Scientific Review of Mountain Lion Hunting and its Effects

Aggressive Trophy Hunting of Mountain Lions May Exacerbate Human Conflicts with Wildlife

This report examines the science behind mountain lion trophy hunting in the western U.S. Wildlife agencies claim this hunting helps control mountain lion populations and reduces conflicts with humans and livestock – recent research suggests otherwise.

by Jim Keen, D.V.M., Ph.D.

How mountain lion trophy hunting increases risks of human-lion conflicts

The Science Breakdown

No science exists, anywhere, to support any claim that Colorado needs to trophy hunt or trap wild cats, to manage anything or to solve anything. This is a recreational pleasure activity; it is not population management of predators or prey; it is not to sustain or conserve populations of predators or prey; it does not make the public safer, and it does not protect pets or livestock or mitigate losses. And it will not produce more deer. Any organization or individual who claims otherwise must be held accountable for the integrity of wildlife science, and wildlife protections and goals in Colorado.

There is a large body of science dating back to 1971 and all the way up through 2023, showing that trophy hunting and trapping of wild cats is not beneficial for wildlife or people. In fact, it is harmful for wild cats, raises risk to livestock and likely to pets, and does nothing to serve the large majority of Coloradans who care about their wildlife and wild places.

Conversely there is zero peer-reviewed science that says we need to or must trophy hunt and/or trap wild cats. Any organization or individual who claims otherwise, must show voters their science (it doesn’t exist) and be held accountable to the highest standards for the integrity of wildlife science, and wildlife protections and goals in Colorado.

Conclusion

CATs offers these 10 science-backed reasons to explain why trophy hunting mountain lions and trapping bobcats does nothing to help produce healthy predators or healthy prey populations or healthy ecosystems in Colorado; it does not “manage” anything, it does not solve anything, but in fact makes things worse with increased risk for human-lion conflict, and artificially altering mountain lion age and sex populations. Coloradans can judge the idea of trophy hunting only as a “pleasure” activity based on values alone, because no science exists to support it as a need or a benefit for anything or anyone besides trophy hunters. It is fair and well-documented to say it has negative costs to wildlife, and to Colorado.

Cat domestication hasn’t changed cats much at all: Your pet house cat has what biologists call “a highly conserved ancestral mammal genome organization,” which means that many stretches of their genome haven’t changed much over evolutionary time. Put simply, domestic cats haven’t changed much since they first evolved. We don’t hunt and eat our housecats, so why would we do this to their exact genetic cousins?

Colorado Bobcat in the snow meets housecat at the window. Photo: Kris Woyna.